https://www.bridgespan.org/insights/pathways-to-greater-social-mobility-...

Executive Summary

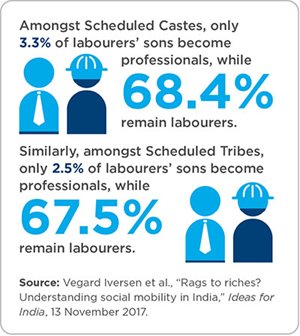

Despite constitutional guarantees, well-intentioned government policies, and dedicated efforts by funders and NGOs, social mobility remains out of reach for most members of India’s 300 million Dalit and Adivasi communities. Abundant evidence shows that these two historically marginalised groups remain at the bottom of a “broken ladder” for upward economic and social mobility. For them, the status quo isn’t working.

Dalit individuals are officially recognised as Scheduled Castes; and Adivasi communities, India’s Indigenous population, are officially designated as Scheduled Tribes. Most experience material poverty throughout their lives: in 8 out of 10 Dalit and Adivasi households, the highest earning member brings home less than Rs 5,000 – roughly $65 – per month.

The Bridgespan Group set out to identify ways for funders and NGOs to support Dalit and Adivasi communities in their quest to improve their economic and social well-being. In short, how can philanthropy partner with NGOs in creating effective ladders of mobility? The answer we heard over and over again in interviews with about 40 NGO leaders, academics, and intermediaries with experience supporting Dalit and Adavasi communities: centre equity to maximise the conditions for social mobility. An equity-centred approach starts by taking the unique histories, aspirations, and needs of Dalit and Adivasi communities into account when funding, designing, and implementing programmes. And it means co-creating solutions with these communities, giving them the training and support to step into their own power.

The Bridgespan Group set out to identify ways for funders and NGOs to support Dalit and Adivasi communities in their quest to improve their economic and social well-being. In short, how can philanthropy partner with NGOs in creating effective ladders of mobility? The answer we heard over and over again in interviews with about 40 NGO leaders, academics, and intermediaries with experience supporting Dalit and Adavasi communities: centre equity to maximise the conditions for social mobility. An equity-centred approach starts by taking the unique histories, aspirations, and needs of Dalit and Adivasi communities into account when funding, designing, and implementing programmes. And it means co-creating solutions with these communities, giving them the training and support to step into their own power.

Equity also means confronting “a history of inequality based on a belief system which has systematically led to intergenerational transfer of privilege, wealth, education, and income for some, and denial of others,” says Professor Amit Thorat of Jawaharlal Nehru University. NGO leaders we interviewed agree. They call India’s historical caste and tribal-based inequity the “elephant in the room,” a complex societal problem that most people are not comfortable talking about.

To date, broad efforts amongst funders to make equity a guiding principle remain nascent in India. Even so, we have profiled a variety of steps that a number of funders and NGOs have taken to put equity at the centre of their work. These efforts fall into three categories: strengthening individual agency and developing community leaders, ensuring quality education and appropriate occupational training, and incorporating equity in grantmaking and programme design. In different ways, all three approaches create pathways for greater economic and social mobility for Dalit and Advisasi individuals.

Equity in other forms is a familiar topic for most funders. Over the past two decades, gender equity has emerged as a broadly accepted concern for the social sector. Based on our analysis of publicly available data, roughly three-quarters of the 62 largest philanthropic organisations operating in India have an intentional gender focus in their programmes. Many of the NGO leaders we spoke with noted that this has spurred the right conversations about the intersection of gender, caste, and tribal issues, resulting in positive action. It is time, they say, to elevate Dalit and Adivasi communities’ concerns for their social and economic equity.

While a number of funders already have taken steps to do just that, most have yet to begin. To date, funders typically focus their support on programmes that aim for immediate benefit to recipients. While the programmes may succeed, failure to centre equity in design and implementation risks overlooking the unique needs of marginalised communities.

Our hope is that our report increases awareness and understanding of the role equity plays in advancing upward mobility. As that happens, more members of Dalit and Adivasi communities will find rungs of the mobility ladder coming within reach.