https://rsf.org/en/2019-world-press-freedom-index-cycle-fear

The RSF Index, which evaluates the state of journalism in 180 countries and territories every year, SEE THE MAPHEREshows that an intense climate of fear has been triggered — one that is prejudicial to a safe reporting environment. The hostility towards journalists expressed by political leaders in many countries has incited increasingly serious and frequent acts of violence that have fuelled an unprecedented level of fear and danger for journalists.

“If the political debate slides surreptitiously or openly towards a civil war-style atmosphere, in which journalists are treated as scapegoats, then democracy is in great danger,” RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire said. “Halting this cycle of fear and intimidation is a matter of the utmost urgency for all people of good will who value the freedoms acquired in the course of history.”

Norway is ranked first in the 2019 Index for the third year running while Finland (up two places) has taken second place from the Netherlands (down one at 4th), where two reporters who cover organized crime have had to live under permanent police protection. An increase in cyber-harassment caused Sweden (third) to lose one place. In Africa, the rankings of Ethiopia (up 40 at 110th) and Gambia (up 30 at 92nd) have significantly improved from last year’s Index.

Many authoritarian regimes have fallen in the Index. They include Venezuela (down five at 148th), where journalists have been the victims of arrests and violence by security forces, and Russia (down one at 149th), where the Kremlin has used arrests, arbitrary searches and draconian laws to step up the pressure on independent media and the Internet. At the bottom of the Index, both Vietnam (176th) and China (177th) have fallen one place, Eritrea (up 1 at 178th) is third from last, despite making peace with its neighbour Ethiopia, and Turkmenistan (down two at 180th) is now last, replacing North Korea (up one at 179th).

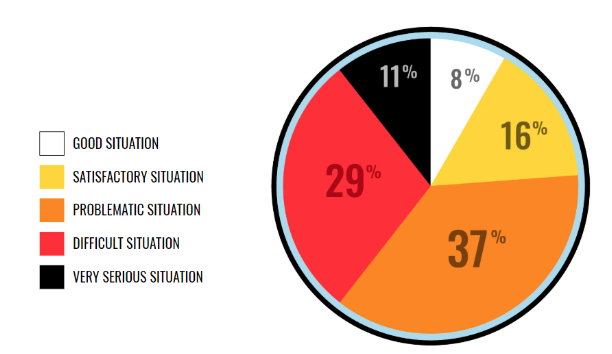

Only 24 percent of the 180 countries and territories are classified as “good” (coloured white on the Press Freedom Map) or “fairly good” (yellow), as opposed to 26 percent last year. As a result of an increasingly hostile climate that goes beyond Donald Trump’s comments, the United States (48th) has fallen three places in this year’s Index and the media climate is now classified as “problematic” (orange). Never before have US journalists been subjected to so many death threats or turned so often to private security firms for protection. Hatred of the media is now such that a man walked into the Capital Gazette newsroom in Annapolis, Maryland, in June 2018 and opened fire, killing four journalists and one other member of the newspaper’s staff. The gunman had repeatedly expressed his hatred for the paper on social networks before ultimately acting on his words.

Threats, insults and attacks are now part of the “occupational hazards” for journalists in many countries. In India (down two at 140th), where critics of Hindu nationalism are branded as “anti-Indian” in online harassment campaigns, six journalists were murdered in 2018. Since the election campaign in Brazil (down three at 105th), the media have been targeted by Jair Bolsonaro’s supporters on both physically and online.

Courageous investigative reporters

In this climate of widespread hostility, courage is needed to continue investigating corruption, tax evasion or organized crime. In Italy (up 3 at 43rd), interior minister and League party leader Matteo Salvini suggested that journalist Roberto Saviano’s police protection could be withdrawn after he criticized Salvini, while journalists and media are subjected to growing judicial harassment almost everywhere in the world, including Algeria (down 5 at 141st) and Croatia (up 5 at 64th).

Abusive judicial proceedings may be designed to gag investigative reporters by draining their financial resources, as in France or in Malta (down 12 at 77th). They could also result in imprisonment, as in Poland (down 1 at 59th), where Gazeta Wyborcza’s journalists are facing possible jail terms for linking the head of the ruling party to a questionable construction project, and in Bulgaria (11th), where two journalists were arrested after spending several months investigating the misuse of EU funds. In addition to lawsuits and prosecutions, investigative reporters are liable to be the targets of every other kind of harassment whenever they lift the veil on corrupt practices. A reporter’s house was set on fire in Serbia (down 14 at 90th), while journalists were murdered in Malta, Slovakia (down 8 at 35th), Mexico (down 3 at 144th) and Ghana (down 4 at 27th).

The level of violence used to persecute journalists who aggravate authorities no longer seems to know any limits. Saudi columnist Jamal Khashoggi’s gruesome murder in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul last October sent a chilling message to journalists well beyond the borders of Saudi Arabia (down 3 at 172nd). Out of fear for their survival, many of the region’s journalists censor themselves or have stopped writing altogether.

<span id="selection-marker-1" class="redactor-selection-marker"></span>

Biggest deterioration in supposedly better regions

Of all the world’s regions, it is the Americas (North and South) that has suffered the greatest deterioration (3.6 percent) in its regional score measuring the level of press freedom constraints and violations. This was not just due to the poor performance of the United States, Brazil and Venezuela. Nicaragua (114th) fell 24 places, one of the biggest in 2019. Nicaraguan journalists covering protests against President Ortega’s government are treated as protesters and are often physically attacked. Many had to flee abroad to avoid being jailed on terrorism charges. The Western Hemisphere also has one of the world’s deadliest countries for the media: Mexico, where at least ten journalists were murdered in 2018. Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s installation as president has reduced some of the tension between the authorities and media, but the continuing violence and impunity for murders of journalists led RSF to refer the situation to the International Criminal Court in March.

The European Union and Balkansregistered the second biggest deterioration (1.7 percent) in its regional score measuring the level of constraints and violations. It is still the region where press freedom is respected most and which is, in principle, the safest, but journalists are nonetheless exposed to serious threats: to murder in Malta, Slovakia and Bulgaria (111th); to verbal and physical attacks in Serbia and Montenegro (down 1 at 104th); and to an unprecedented level of violence during the Yellow Vest protests in France (down 1 at 32nd). Many TV crews did not dare cover the Yellow Vest protests without being accompanied by bodyguards, and others concealed their channel’s logo. Journalists are also being openly stigmatized. In Hungary (down 14 at 87th), officials in Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s party Fidesz continue to refuse to speak to journalists who are not from media that are friendly to Fidesz. In Poland, the state-owned media have been turned into propaganda tools and are increasingly used to harass journalists.

Although the deterioration in its regional score was smaller, the Middle East and North Africa region continues to be the most difficult and dangerous for journalists. Despite a slight fall in the number of journalists killed in 2018, Syria (174th) continues to be extremely dangerous for media personnel, as does Yemen (down 1 at 168th). Aside from wars and major crises, as in Libya (162nd), another major threat hangs over the region’s journalists – that of arbitrary arrest and imprisonment. Iran (down 6 at 170th) is one of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists. Dozens of journalists are also detained in Saudi Arabia, Egypt (down 2 at 163rd) and Bahrain (down 1 at 167th), many of them without trial. And when they are tried, the proceedings drag on interminably, as in Morocco (135th). The one exception to this gloomy picture is Tunisia (up 15 at 97th), which has seen a big fall in the number of violations.

Africa registered the smallest deterioration in its regional score in the 2019 Index, but also some of the biggest changes in individual country rankings. After a change of government, Ethiopia (110th) freed all of its detained journalists and secured a spectacular 40-place jump in the Index. And it was thanks to a change of government that Gambia (up 30 at 92nd) also achieved one of the biggest rises in this year’s Index. But new governments have not always been good for journalists. Tanzania (down 25 at 118th) has seen unprecedented attacks on the media since John “Bulldozer” Magufuli’s installation as president in 2015. Mauritania (down 22 at 94th) also fell sharply, in large part because the blogger Mohamed Cheikh Ould Mohamed Mkhaitir is being held incommunicado though he should have been freed more than a year and a half ago, when his death sentence for apostasy was commuted to a jail term. In this continent of contrasts, bad situations have continued unchanged in some countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo (154th) was again the country where RSF registered the most violations in 2018, while Somalia (164th) continued to be Africa’s deadliest country for journalists.

The Eastern Europe and Central Asiaregion continues to rank second from last in the Index, the position it has held for years, despite an unusual variety of changes at the national level and a slight improvement in its regional score. Some of the indicators used to calculate the score improved, while others deteriorated. Of the latter, it was the legal framework indicator that worsened most. More than half of the region’s countries are still ranked near or below 150th in the Index. The regional heavyweights, Russia and Turkey, continue to persecute independent media outlets. The world’s biggest jailer of professional journalists, Turkey, is also the world’s only country where a journalist has been prosecuted for their Paradise Papers reporting. In this largely ossified region, rises are rare and deserve mention. Uzbekistan (up 5 at 160th) has ceased to be coloured black (the mark of a “very bad” situation) after freeing all the journalists who were jailed under the late dictator, Islam Karimov. In Armenia (up 19 at 61st), the “velvet revolution” has loosened the government’s grip on TV channels. The size of its rise was facilitated by the fact that this is a very volatile part of the Index.

With totalitarian propaganda, censorship, intimidation, physical violence and cyber-harassment, the Asia-Pacificregion continues to exhibit all of the problems that can beset journalism and, with a virtually unchanged regional score, continues to rank third from last. The number of murdered journalists was extremely high in Afghanistan (121st), India and Pakistan (down 3 at 142nd). Disinformation is also becoming a big problem in the region. As a result of the manipulation of social networks in Myanmar, anti-Rohingya hate messages have become commonplace and the seven-year jail sentences imposed on two Reuters journalists for trying to investigate the Rohingya genocide was seen as nothing out of the ordinary. Under China’s growing influence, censorship is spreading to Singapore (151st) and Cambodia (down 1 at 143rd). In this difficult environment, the 22-place rises registered by both Malaysia (123rd) and Maldives (98th) highlight the degree to which political change can radically transform the climate for journalists, and how a country’s political ecosystem can directly affect press freedom.

Published annually by RSF since 2002, the World Press Freedom Index measures the level of media freedom in 180 countries. It assesses the level of pluralism, media independence, the environment for the media and self-censorship, the legal framework, transparency, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information. It does not evaluate government policy.

The global indicator and the regional indicators are calculated on the basis of the scores registered for each country. These country scores are calculated from the answers to a questionnaire in 20 languages that is completed by experts throughout the world, supported by a qualitative analysis. The scores measure constraints and violations, so the higher the score, the worse the situation. Because of growing awareness of the Index, it is an extremely useful advocacy tool.

Add new comment