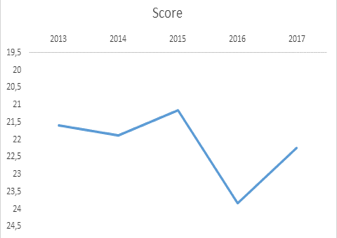

Ranked 160th out of 180 in the 2017 Index after falling four places, Burundi is the first of the 21 countries in the black zone. President Pierre Nkurunziza launched a fierce crackdown in 2015 against media outlets that covered a coup attempt after his decision to run for a third term. Burundi is now locked in a crisis and media freedom is dying. Charged with supporting the coup, dozens of journalists have fled into exile. For those that remain, working is almost impossible without toeing the government line. The all-powerful National Intelligence Service (SNR) interrogates, arrests, and mistreats reporters and editors at will. Editors are told to “correct” articles that cause displeasure. No holds are barred in the regime’s war on any form of opposition or criticism. Information is manipulated and journalists are beaten. One journalist, Jean Bigirimana, has disappeared The other two countries that have entered the Index’s black zone are both from the region with the worst score – the Middle East. Many journalists have been imprisoned in both countries– 24 in Egypt and 14 in Bahrain – and they both detain their journalists for very long periods of time. In Egypt (down 2 at 161st), Mahmoud Abou Zeid, a photojournalist also known as Shawkan, has been held arbitrarily for more than three years without being tried. His crime was to have covered the violent dispersal of a demonstration organized by the Muslim Brotherhood, which is now branded as a terrorist organization. Freelancer Ismail Alexandrani has been in pre-trial detention since November 2015although a judge ordered his release in November 2016. Regardless of the law, the regime led with an iron fist by Gen. Al-Sisi tolerates no criticism, suppresses protests, shamelessly erodes media pluralism,attacks the journalists’ union, and encourages self-censorship amongst reporters on a daily basis. The situation is no better in the Kingdom of Bahrain (down 2 at 164th), which is back in the black zone where it always was, except for a brief respite in 2016. Dissidents or independent commentators such asNabeel Rajab, the head of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, pay a high price for daring to criticize the authorities in tweets or interviews. The regime intensified its repressive methods in 2011, when it feared it might be overthrown. Any content or media suspected of posing a threat to the country’s unity is simply suppressed, and detained journalists face the possibility of long jail terms or even life imprisonment. At the other end of the black zone, three countries have monopolized the last three places for the past 12 years. Ever since the 2005 Index, North Korea, Turkmenistan, and Eritrea have consistently suppressed and crushed all divergence from the state propaganda. Eritrea (up 1 at 179th) has for the first time in ten years relinquished the bottom place to North Korea, even if there has been no fundamental change in the situation in this aging dictatorship where freely reported news and information have long been banned. The media, like the entire society, are still totally under President Issayas Afeworki’s arbitrary thumb. The Eritrean government continues to enforce lifetime conscription and to detain dozens of political prisoners and journalists arbitrarily. In 2016, a few foreign media crews were nonetheless allowed into the country to do reports, under close escort. North Korea (down 1 at 180th), now ranked last in the Index, has also shown more flexibility towards the foreign media. More foreign reporters have been allowed to cover official events and, in September 2016, Agence France-Presse was even able to open a bureau in Pyongyang. These developments might give the impression of more openness, but in fact there is no desire for real change. The information available to the foreign media is still meticulously controlled and the population is kept in ignorance and terror.Listening to a radio station based outside the country can lead straight to a concentration camp. North Korea continues to be a Cold War-era dictatorship. Turkmenistan, another hangover from a previous era, has held on to its 178th position. Any criticism of the Arkadag (“Father Protector”) is inconceivable is this former Soviet Republic. The state has total control over the media and continues to intensify its harassment of the few remaining correspondents of foreign-based independent media, who are forced to work clandestinely. The government has continued its campaign to remove all satellite dishes, denying the public of one of its last chances to access freely reported news. Former Soviet republics have produced many of the dictators found on the Index. Examples include Azerbaijan (up 1 at 162nd), where trumped-up charges are used to jail journalists, and Uzbekistan (down 3 at 169th), which is a model of institutionalized censorship although the new president’s behavior has raised hopes of improvement after the widespread use of torture under his predecessor. In Asia, China (176th), Vietnam (175th), and Laos (170th) have always languished near the bottom of the Index alongside North Korea (180th). But that is not all they have in common. They are all also totalitarian communist regimes in which journalists take their orders from the Party and, in China especially, citizen journalists and bloggers are prosecuted and jailed if they dare to offer the least criticism of the Party-State. The perpetuation of a Soviet-style communist regime is the reason why Cuba (down 2 at 173rd) is more hostile to media freedom than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere. The state’s monopoly of news and information did not end with the death of Fidel Castro, who will be remembered not only as the father of the Cuban revolution but also as one of the planet’s worst press freedom predators. Aside from Eritrea and Burundi, already mentioned, three of the other four African countries in the Index’s black zone have regimes that are at the very least autocratic if not brutal dictatorships. Both Omar al-Bashir in Sudan (174th) and Teodoro Obiang Nguema in Equatorial Guinea (down 3 at 171st) constantly crack down on the least dissent in order to hold on to the power they acquired by force in the last century. Both are on RSF’s list of press freedom predators and both continued, in various ways, to curtail freedom of information, expression, and thought in 2016. In Djibouti, which held on to its 172nd position in the 2017 Index, President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh has also deployed a significant repressive arsenal against the media. After steadily depriving his country of independent and opposition media, the iron-fisted Guelleh found it fairly easy to amend the constitution in order to run for a fourth consecutive term. Defense of religion, morality, and the established order are the grounds usually given in the Middle East for violating media freedom.The Islamic Republic of Iran (up 4 at 165th) imprisons journalists arbitrarily by the dozens on the pretext of combatting “obscenity” or threats to national security. Prison conditions are so bad that many of them go on hunger strike in protest. The Iranian regime imposes inhuman and medieval punishments such as flogging. For “insulting Islam,” Saudi Arabia (down 3 at 168th) also sentenced the blogger Raif Badawi to flogging as well as ten years in prison. Both King Salman bin Abdulaziz, who took over the reins of the Saudi dynastic monarchy in 2015, and the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, hold distinguished positions in the ranks of RSF’s press freedom predators. Dictatorships and other totalitarian regimes obviously throttle media freedom and pluralism, but wars and latent conflicts are also devastating and can quickly drive a country down into the lower regions of the Index and keep it there for years. Six years after the start of a bloody civil war, Syria is now the world’s deadliest country for journalists and is stuck at its 177th position. Nothing has been done to protect journalists from the insane barbarity of its dictator and fanaticized Jihadi armed groups that stop at nothing. Journalists are also caught in the crossfire in Yemen (166th). Even if fewer were killed in 2016, which accounts for Yemen’s four-place rise, journalists risk being abducted and held hostage by the Houthi rebels or by Al-Qaeda. They also risk being killed in air strikes by the Saudi-led Arab coalition. Chaos is equally dangerous for journalists in Libya (down 1 at 163rd), which is torn by armed clashes between rival factions and is on the verge of imploding. Three more journalists died in 2016 covering fighting in Sirte and Benghazi. Although the toll of dead and missing has fallen, journalists still face endless threats because crimes of violence against them go unpunished. So too in Somalia (167th), where the fragility of the state contributes to the dangers for journalists, who are the victims not only of shootings and bombings by Al-Shebaab, but also persecution by what remains of governmental authority. It is clear from the 2017 Index that the frequency of media freedom violations is on the rise (see our release entitled Tipping point?) and this is reflected inter alia in a 7% increase over the past five years in the number of countries located in the “red zone” (where the situation is classified as “bad”). This in turn suggests that a rapid increase in the number of countries in the “black zone” may also be imminent. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo – headed by Joseph Kabila, another press freedom predator – has been falling steadily since 2002, when it was ranked 113th in the first Index published by RSF. After falling two more places in the past year, it is ranked 154th in the 2017 Index and is steadily approaching the “black zone.” Similarly, South Sudan (down 5 at 145th) has fallen more than 20 places in the past five years because of its civil war and seems to be heading inexorably down to join the countries in the worst category. Turkey is one of the most alarming cases in the 2017 Index. Ranked 155th after falling four more places in the past year, it has fallen a total of 57 places in the past 12 years. The coup attempt in July 2016swept aside the last restraints on the government in its war against critical media. The ensuing state of emergency has allowed the authorities to disband dozens of media outlets at the stroke of pen month after month, reducing pluralism to a handful of low-circulation newspapers. More than 100 journalists have been detained without trial, turning Turkey into the world’s biggest prison for media professionals. Mexico is another country that stood out last year. Ranked 75th in RSF’s 2002 Index, it has fallen almost 75 places in the past 15 years and is ranked 147th in the 2017 Index after 10 more journalists were murdered in 2016 (and another spate of killings in March 2017). It is riddled by corruption and violent organized crime, especially at the local level. In the states of Veracruz, Guerrero, Michoacán, and Tamaulipas, it is extremely dangerous for journalists to cover sensitive subjects, especially as impunity for crimes of violence against the media feeds a vicious circle that continues year after year. In terms of level of risk for journalists, Mexico is nowadays only just behind Syria and Afghanistan, which is down at 120th. The courageous efforts of Afghanistan’s journalists and their determination to fulfil their reporting mission are frustrated by the constant decline in the security situation resulting from the Taliban and Islamic State insurrections, which have turned entire provinces into news and information “black holes.” Only the government’s declared readiness to create protective mechanisms for journalists has prevented Afghanistan from falling further in the Index. RSF’s latest World Press Freedom Index highlights the danger of a tipping point in the state of media freedom, especially in leading democratic countries. (Read our analysis entitled Journalism weakened by democracy’s erosion.) Democracies began falling in the Index in preceding years and now, more than ever, nothing seems to be checking that fall. The obsession with surveillance and violations of the right to the confidentiality of sources have contributed to the continuing decline of many countries previously regarded as virtuous. This includes the United States (down 2 places at 43rd), the United Kingdom (down 2 at 40th), Chile (down 2 at 33rd), and New Zealand (down 8 at 13th). Donald Trump’s rise to power in the United States and the Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom were marked by high-profile media bashing, a highly toxic anti-media discourse that drove the world into a new era of post-truth, disinformation, and fake news. Media freedom has retreated wherever the authoritarian strongman model has triumphed. Jaroslaw Kaczynski’s Poland (54th) lost seven places in the 2017 Index. After turning public radio and TV stations into propaganda tools, the Polish government set about trying to financially throttle independent newspapers that were opposed to its reforms. Viktor Orbán’s Hungary (71st) has fallen four places. John Magufuli’s Tanzania (83rd) has fallen 12. After the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey (down 4 at 155th) swung over into the authoritarian regime camp and now distinguishes itself as the world’s biggest prison for media professionals. Vladimir Putin’s Russia remains firmly entrenched in the bottom fifth of the Index at 148th. “The rate at which democracies are approaching the tipping point is alarming for all those who understand that, if media freedom is not secure, then none of the other freedoms can be guaranteed,” RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire said. “Where will this downward spiral take us?” In the emerging new world of media control, even the top-ranked Nordic countries are slipping down the Index. After six years at the top, Finland (down 2 at 3rd) has surrendered its No. 1 position due topolitical pressure and conflicts of interests. The top spot has been taken by Norway (up 2 at 1st), which is not a European Union member. This is a blow for the European model. Sweden has risen six places to take 2nd position. Journalists continue to be threatened in Sweden but the authorities sent a positive signal in the past year by convicting several of those responsible. The cooperation between the police and certain media outlets and journalists’ unions was also seen as a step forward in combatting the threats. At the other end of the Index, Eritrea (179th) has surrendered last place to North Korea for the first time since 2007, after allowing closely-monitored foreign media crews into the country. North Korea (180th) continues to keep its population in ignorance and terror – even listening to a foreign radio broadcast can lead to a spell in a concentration camp. The Index’s bottom five also include Turkmenistan (178th), one of the world’s most repressive and self-isolated dictatorships, which keeps increasing its persecution of journalists, and Syria (177th), riven by a never-ending war and still the deadliest country for journalists, who are targeted by both its ruthless dictator and Jihadi rebels. (See our analysis entitled 2017 Press Freedom Index – ever darker world map.) Media freedom has never been so threatened and RSF’s “global indicator” has never been so high (3872). This measure of the overall level of media freedom constraints and violations worldwide has risen 14% in the span of five years. In the past year, nearly two thirds (62.2%) of the countries measured* have registered a deterioration in their situation, while the number of countries where the media freedom situation was “good” or “fairly good” fell by 2.3%. The Middle East and North Africa region, which has ongoing wars in Yemen (down 4 at 166th) as well as Syria, continues to be the world’s most difficult and dangerous region for journalists. Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the second worst region, does not lag far behind. Nearly two third of its countries are ranked below or around the 150th mark in the Index. In addition to Turkey’s downward spiral, 2016 was marked by a clampdown on independent media in Russia, while the despots in such former Soviet republics as Tajikistan (149th), Turkmenistan (178th), and Azerbaijan (162nd) perfected their systems of control and repression. The Asia-Pacific region is the third worst violator overall but holds many of the worst kinds of records. Two of its countries, China (176th) and Vietnam (175th), are the world’s biggest prisons for journalists and bloggers. It has some of the most dangerous countries for journalists: Pakistan (139th), Philippines (127th) and Bangladesh (146th). It also has the biggest number of “press freedom predators” at the head of the world’s worst dictatorships, including China, North Korea (180th), and Laos (170th), which are news and information black holes. Africa comes next, where the Internet is now routinely disconnected at election time and during major protests. More than five points separate then the African region from the Americas, where Cuba (down 2 at 173rd) is the only country in the black (i.e. “very bad”) zone of the Index, which is otherwise reserved for the worst dictatorships and authoritarian regimes of Asia and the Middle East. Finally, the European Union and Balkans region continues to be the one where the media are freest, although its regional indicator (of the overall level of constraints and violations) registered the biggest increase in the past year: +3.8%. The differences in regional indicator change over the past five years are particularly noticeable. The European Union and Balkans indicator rose 17.5% over the past five years. During the same period, the Asia-Pacific indicator increased by only 0.9%. The word’s regions (in descending order of respect for media freedom) Nicaragua (down 17 at 92nd) distinguished itself in 2017 by falling further than any other country on the Index. For the independent and opposition media, President Daniel Ortega’s controversial re-election was marked by many cases of censorship, intimidation, harassment, and arbitrary arrest. Tanzania (down 12 at 83rd), where President John “Bulldozer” Magufuli keeps tightening his grip on the media, also suffered a significant fall. Amid all the decline, rises in two countries seem particularly promising and will hopefully continue. After ridding itself of its autocratic president, Gambia (up 2 at 143rd) has rediscovered uncensored newspapers and is planning to amend legislation that is restrictive for the media. The historic peace accord in Colombia (up 5 at 129th) has ended a 52-year armed conflict that was a source of censorship and violence against the media. No journalists were killed in 2016, making it the first time in seven years that journalists survived their work. However, other sizeable jumps in the 2017 Index are probably deceptive. Italy (52nd) has risen 25 places after acquitting several journalists including the two Italian journalists who were tried in the VatiLeaks 2 case. But it continues to be one of the European countries where the most journalists are threatened by organized crime. France has risen six places to 39th position but it was simply recovering from the exceptional fall it suffered in the 2016 Index because of the Charlie Hebdo massacre. It is a country where journalists struggle to defend their independence in an increasingly violent and hostile environment. Excepting the 2016 Index, France’s latest score (22.24) is its worst since 2013, a decline that is due inter alia to problems arising from businessmen using the media as a source of influence. RSF welcomed a new law on media independence but it did not suffice to significantly modify the situation. In Asia, the Philippines (127th) rose 11 places, partly because of a fall in the number of journalists killed in 2016, but the insults and open threats against the media by President Rodrigo Duterte, another new strongman, do not bode well. Evolution in France’s score Published annually by RSF since 2002, the World Press Freedom Index measures the level of media freedom in 180 countries, including the level of pluralism, media independence, and respect for the safety and freedom of journalists. The 2017 Index takes account of violations that took place between January 1st and December 31st of 2016. The global indicator and the regional indicators are calculated based on the scores assigned to each country. The country scores are calculated from the answers to a questionnaire in 20 languages that is completed by experts throughout the world, supported by a qualitative analysis. The scores and indicators measure the level of constraints and violations, so the higher the figure, the worse the situation. Because of growing awareness of the Index, it is an extremely useful and increasingly influential advocacy tool. * The term “country” is used in its ordinary sense, without any special political meaning or allusion to certain territories.

https://rsf.org/en/2017-press-freedom-index-ever-darker-world-map

I. Additions to the black list

EGYPT

AND BAHRAIN, PRISONS FOR JOURNALISTS

II. The last of the last

III. Predators on all continents

FROM TOTALITARIANISM TO AUTOCRACY

IV. War and crises, also enemies of journalists

V. A non-exhaustive black list

TURKEY, MEXICO, AND AFGHANISTAN IN THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL

I. Democracies falling, advent of strongmen

II. Norway first, North Korea last

MEDIA FREEDOM NEVER SO THREATENED

III. Rises, falls, and illusory improvements

Add new comment