https://www.macfound.org/annual-report/2018/president-essay/

From time to time, I share my thoughts about how MacArthur is navigating an evolving local, national, and global context. I try to say something new, perhaps insightful, but always with optimism that the world can be a better place.

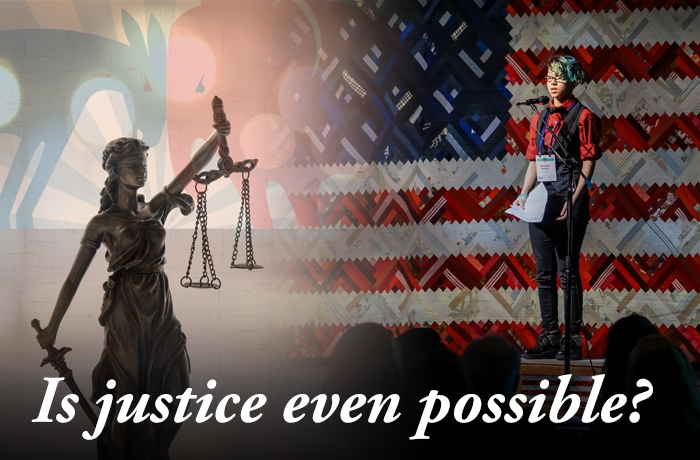

This time, my focus is on our mission, on our commitment to building a more just, verdant, and peaceful world, and I am concerned.

In breathtaking convergence, bedrock values, longstanding alliances, workable regimes, standards of decency and care, scientific consensus, and much more are under attack. As philanthropy rushes to respond to new imperatives, or doubles down on longstanding priorities that matter even more today, I find myself eager for discussion and exchange. As we consider this extraordinary time around the world, in our country, here in Chicago, and even within MacArthur, I want to reach out, connect and learn, and work together on hard questions with no easy answers.

The world is more just when actions are moral, rational, equitable, and fair. MacArthur’s mission of a more just, verdant, and peaceful world leads with justice; without it, universal human dignity, equitable opportunity, and shared prosperity are not possible. Of course, we are not alone in our concern for justice. In one of many examples, a fellow foundation leader has urged us all to reject the seduction of a great America and actively pursue an America that is just.

And yet, how does one forge a path toward justice in a political and policy environment that has unleashed inner demons and accelerated a decline in trust in institutions of all kinds and in those who lead them? Ubiquitous platforms that hold the promise of community, collaboration, and constructive engagement also foster a free market of unbridled rhetoric. Protected by anonymity, and increasingly in the open, people are encouraged to express their hatreds and insecurities, to assert their individual or tribal interests. Antipathy toward others is celebrated as candor, and, in a world of digital intimacy, and even in the public square, we have become strangers without connection.

Some believe that the way to defeat us is to manipulate and divide us. If we do not see humanity in each other, we do not need enemies. We will attack strangers and our neighbors ourselves.

I am wondering if justice is possible without three foundational imperatives: a commitment to the common good; empathy and recognition of our shared humanity; and investment and trust in the institutions of accountability.

Commitment to the Common Good

Is justice possible without a commitment to the common good—where each individual has a stake in the betterment of society as a whole?

These days, it feels like a zero-sum game. An America that is first and only does not acknowledge the contribution, even the sacrifice, our country must make to help ensure a better world for all. One example: we can pull out of the Paris climate agreement to protect segments of our business sector, but how can we thrive if environmental conditions are worsening here at home and around the world?

Increasingly, public dialogue is fraught with notions of tribalism, nativism, hyper-nationalism, and annihilation of the other. Drowned out or characterized as weak are calls for shared responsibility, common cause, principled compromise, or short-term sacrifice for long-term gain that benefits all. Our own country’s history embodies this tension between individualism and pluralism. Today, the pendulum seems to be swinging toward the former, putting justice further out of reach.

Investment and Trust in Institutions of Accountability

Is justice possible without institutions through which accountability is exercised?

Like individuals, institutions are imperfect. Under attack are the news media; political parties and the political process; law enforcement and the courts; academia, science, and other sources of data; and more. Today, the challenge is to their very existence, which makes the essential task of investing in their improvement even harder.

Trust in those institutions is a bigger challenge, as it requires them to be respectful, fair, transparent, inclusive, and humble, and to understand that trust must be earned, again and again, each and every day.

Investment in these institutions, and an effort to secure and sustain trust, are essential; without institutions of accountability, promoting and protecting the conditions under which justice can thrive is then the impossible responsibility of every person.

And, yet.

Contrasting these stark questions is a persistent belief that we can engage our neighbors; welcome strangers; open our minds to the views, needs, hopes and dreams of others; and wake each day determined to listen earnestly, work differently, sustain our energy for constructive change, and try again to make sense of what seems nonsensical. Why do I believe this?

Hope and Optimism

While I find that there is a lot to be deeply anxious and even angry about these days, and perhaps the easiest response is to turn inward and to withdraw, hope persists. I use this word carefully. Hope and optimism are not the same. Hope is a feeling of expectation and a desire for a certain thing to happen. Optimism is laced with confidence that something will happen.

For me, hope comes from the incredible number of women running for political office, to get inside the political system and make it work better for more people. I also am encouraged by the vigor of social movements. In the U.S.: Black Lives Matter; #MeToo; sanctuary cities and campuses; efforts to defend science; anti-Islamophobia activism; LGBTQIA advocacy; the Dreamers; the Women’s March; and the inspiring leadership of young people as they demand that adults look beyond their “thoughts and prayers” as a response to gun violence and take action to secure a better future.

Global examples abound as well. In Mexico, there was a vigorous 63 percent turnout in the recent presidential contest, and voters elected the first female mayor of Mexico City. In Nigeria, as a result of the #NotTooYoungToRun campaign, a constitutional amendment has reduced the age to run for key positions in the country.

I have optimism as well. Last year, through our global competition, 100&Change, MacArthur awarded $100 million to a partnership of Sesame Workshop and the International Rescue Committee that will provide early education and the foundation for a better future for young children displaced by conflict in the Middle East. To encourage bold, expansive thinking, and to fulfill our commitment to supporting the ambitions of others, 100&Change solicited proposals on any issue from anywhere in the world. More than 1,900 organizations and collaborations came forward with solutions. As important as the award, 100&Change demonstrated that, in a world fraught with challenge, solutions are possible, propelled by brilliant, caring people seeking resources to help other people and the planet.

Courage

Examples of courage abound; three stand out. In Mexico, families of the more than 35,000 “disappeared” courageously confront the government to demand an organized, official, and effective search and investigation. They work side by side with legislators and authorities to demand improvements to the justice system and to prevent further atrocities. With courage as well, in one of the most dangerous countries in the world for their profession, Mexican journalists continue to risk their lives to report on hard issues, including organized crime, government collusion, violence, and corruption—all of which contribute to the country’s human rights crisis. Families and seasoned professionals alike are taking enormous risks because of the scale of inhumanity and impunity and their determination that things can be better.

A very different example exists here in the U.S. In Montgomery, Alabama, at a time when racial fear and resentment are being cynically and unconscionably provoked and stoked, MacArthur Fellow Bryan Stevenson led the effort to create the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice. This brave and compelling place and experience unflinchingly demands that we confront the racial terrorism of our history and consider its present-day face.

Even closer to home, and at a much different, more intimate scale, four African-American women came to my Chicago office to see me. Leaders of important nonprofits, they did not ask for funding, they came to talk. Despite their tremendous work, they feel they cannot catch their breath. They wonder how they can support the needs of their staff; their clients, customers or charges; an aching community; accomplished colleagues and their projects—and also plan and provide for the future and support themselves and each other. They feel their leadership is under-appreciated, needs to be constantly reaffirmed, and has a particular quality not acknowledged by philanthropy.

They value generative, generous leadership that looks beyond the success of their own institution to the success of the community at large. As a matter of principle, they lift up each other, their neighbors, and their sister institutions. They ignored the power dynamic and risk inherent in the grantor-grantee relationship and asked to be heard and valued.

Inspired by conversations with these courageous women and others, we have refined our criteria for Chicago organizations awarded capacity-enabling institutional support grants:

These critical organizations have a clear vision, mission, and goals. They are acknowledged as successful by the communities they serve, and their leaders generously share their time and expertise with others. These individuals and their organizations are resilient, generative, compassionate partners. They help educate, strengthen, and connect others, with a goal of tackling barriers and increasing the confidence, stability, power, and effectiveness of the community as a whole.

Conclusion

Even as I question whether justice is even possible, here at the Foundation we are working to advance what I call the just imperative. It is a formal effort to ensure that our decisions and actions enhance the conditions in which justice can thrive, rejecting or challenging those that reinforce an unjust status quo or produce unjust outcomes. It is the framework through which we, like many others, are trying to live the values of diversity, equity, and inclusion in our internal operations, in our organizational culture, and in every program where we are investing our resources and trying to help bring about change. It is hard work; we will not always get it right. To live our mission of a world that is more just requires that we do it.

Is justice possible? The answer has to be yes, but it is certainly not inevitable, maybe not even probable. So, together we need to increase the odds.

Add new comment