Ideas matter. Perhaps more than any other large international organization, the World Bank–which brands itself as “the knowledge bank” and is staffed by thousands of Ph.D. economists–is highly attentive to new empirical research, and frequently swayed by the intellectual fads of academic economics.

For the past 35 years, the World Bank has hosted the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, or ABCDE, showcasing internal and external research relevant to the Bank’s mission of a world free of poverty.

This year, on July 9 and 10, CGD co-hosted the conference together with the World Bank. If you missed it, the full program, video, transcripts, and most of the papers or presentations are online. But here are some points that jumped out at us.

Day 1

The World Bank is wrestling with how to balance the fights against poverty and climate change

The theme of the conference, and in particular the first day, was “the Great Incoherence”, a broad reference to the scale of the international community’s ambitions and the paltry resources devoted to them. But World Bank Chief Economist Indermit Gill also tied the “incoherence” theme to specific contradictions in the Bank’s new climate agenda:

- The trade-off between financing climate mitigation in middle-income countries and poverty alleviation in low-income countries

- A new round of trade protectionism which threatens to undermine the green transition

- The hypocrisy of historically high emitters in the West pushing the World Bank not to lend for natural gas projects in countries with limited energy access and scant emissions

In the morning of the first day, Larry Summers declared that “the world is on fire”: climate, conflict, commodity prices, militarization, high interest rates, debt overhang, and–of particular relevance for the World Bank’s clients–declining foreign aid for general budget support. In response, a recent G-20 commission co-chaired by Summers called for massively scaling up the size of the World Bank and other multilateral development banks.

But the conventional wisdom is that to win support for a bigger World Bank from its shareholders, the Bank needs to show it has a pivotal role to play in addressing climate change, while also stretching its existing resources further and improving its efficiency.

World Bank President Ajay Banga talked about how he intends to do that. He discarded his prepared remarks about development economics and delivered his stump speech about how to reform the World Bank. His first goal is to speed up the 19 months it takes the World Bank to get from a project idea to loan approval. Another major priority is crowding in private finance. He floated the idea of bundling renewable energy and water projects in Africa to make them viable investment vehicles for Larry Fink at Blackrock.

Once taboo at the World Bank, a new empirical economics of industrial policy is emerging

If you expected a World Bank session on industrial policy to rail against state intervention and preach the efficiency of unfettered markets, that is not what ABCDE delivered. Indeed, listening to World Bank economists talk about empirical evidence on how to do industrial policy well, Pritish Behuria from Manchester University worried about the neglect of political economy.

But the empirical results were striking. David McKenzie summarized a growing body of experimental work on subsidies to small and medium enterprises in the developing world. His paper has more caveats than fit here, but he delivered some surprisingly positive messages:

- Government can’t always pick winners, but sometimes can filter out firms that definitely won’t benefit from subsidies

- There is real “additionality” sometimes, not just subsidizing firms to do what they would’ve done anyway

- Subsidies can sometimes grow the market, not just the market share of one firm

Grants to SMEs are a pretty minimalist form of industrial policy. But Tristan Reed noted that the World Bank is now nominally committed to promoting “key sectors” in its client countries. That raises the question: what’s a “key” sector? He proposed two identifying characteristics: revealed comparative advantage, i.e., sectors where countries have already demonstrated some capability; and low global market share, putting focus on sectors where there’s room to grow.

Perhaps the deepest skepticism of industrial policy came on Day 2 from Raghuram Rajan, presenting his book “Breaking the Mold: India’s Untraveled Path to Prosperity.” Rajan argued that India was wasting its efforts trying to climb the ladder of manufacturing exports, and in particular to build an internationally competitive microchip industry. Echoing a recent paper by Dani Rodrik and Joe Stiglitz, Rajan argued this traditional growth path was closing, and India’s comparative advantage lies now in services exports.

To compete globally in services, Rajan argued, India needs to invest less in industrial subsidies and more in the human capital of its workforce. At present, “India doesn’t have a single university in the top hundred” globally.

Sovereign debt dominates the development agenda, but China (not the World Bank) holds the keys

Debt distress is likely to stymie many of the World Bank’s grand ambitions for its poorer client countries. While the ABCDE session didn’t offer a lot in the way of solutions, it was informative about the state of the world we’re in. Enrico Mallucci showed that countries default at about the same rate on domestic and external debt, but on much harsher terms for domestic creditors. And in a not terribly surprising finding, Rong Qian showed that default rates are higher in countries with poor governance indicators.

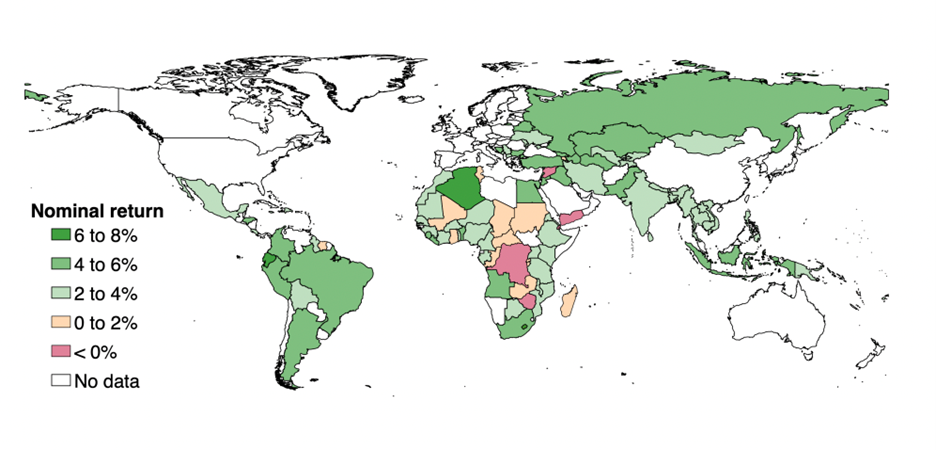

Figure 1. The realized financial return on China’s Belt-and-Road lending

Source: Reproduced from Franz et al (2024)

China is the pivotal player in negotiating debt relief for many low- and middle-income countries under fiscal stress. But the Belt and Road lending portfolio is fairly opaque. Christoph Trebesch presented some fairly simple, but previously undocumented facts about China’s trillion dollar lending portfolio in the developing world:

- Restructuring of Chinese loans is rare, and when they happen offer haircuts of only about 12 percent compared to 36 percent during restructurings across all private external creditors.

- The net financial return on Chinese lending works out to about 1.7 percent per annum. That’s a lot better than the 0.1 percent return on U.S. Treasuries over the same period, but far below the 8.1 percent return on global equities or even the 4.6 percent return on Chinese equities.

Financial incentives can help address climate change, but financial markets may not do it on their own

In the opening plenary session, CGD’s incoming President Rachel Glennerster noted that efforts to pay people to plant trees in the UK were wasteful, and that the same money would go much further in Uganda.

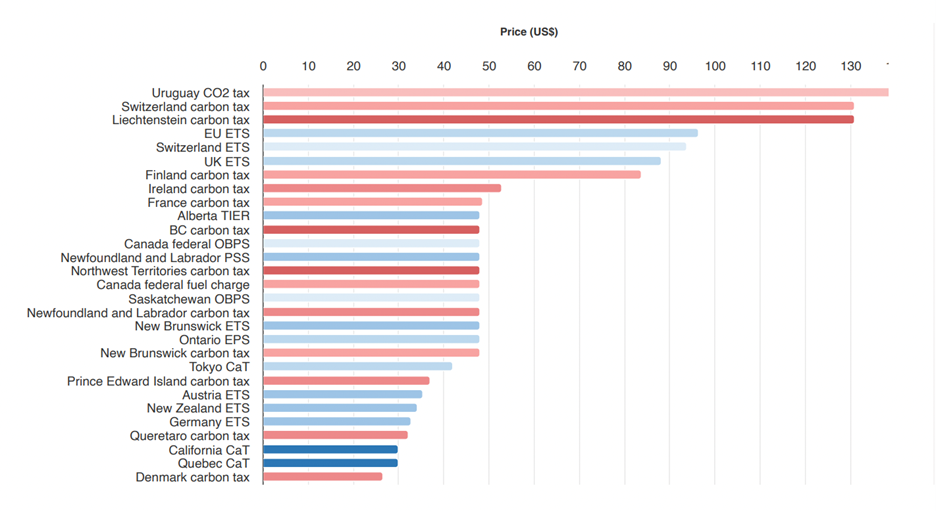

In a similar vein, José Scheinkman noted the Amazon rainforest has lost an area the size of Texas. He and his coauthors calculate that payments of $25 per ton of carbon would be enough not just to stop the decline in forest area, but to recover that entire lost area within a dozen years. That compares quite favorably to carbon prices offered in various schemes around the world.

Figure 2. “Economic efficiency implies all carbon prices should be the same”

Source: Reproduced from Scheinkman (2024) ABCDE presentation.

The rest of the session focused on how financial markets, left to their own devices, price in climate risk. Lee Seltzer showed evidence that bond markets do factor in climate risk: post-Paris, brown firms in strict regulatory jurisdictions experienced larger yield spreads. But there may be limits to market discipline here. Manthos Delis presented evidence that, yes, bond markets price in the risk that reserves held by fossil-fuel firms end up stranded, but bank lenders do not.

Innovation remains woefully underfunded relative to its economic returns

Glennerster made the case that the World Bank didn’t just need more money, it needed to use the money it has more efficiently. One way to do that, she argued, was investing more in innovation, and specifically shaping innovation in the direction of the interests of the poor. The classic example is research on “orphaned” diseases that exist only in poor countries and offer little economic return to pharmaceutical companies, but the same point stands for research on climate resilient seeds for African crops.

Michael Kremer picked up this theme in his keynote address. Academic research inevitably concludes that “more research is needed”. But when Kremer says it, he means it in a more literal sense. His keynote address made the case that investments in innovation–including experimental research by academic economists–are a central driver of development progress, and pay for themselves many times over.

He highlighted the examples of weather forecasts for smallholder farmers in India, and microcredit for water tanks in Kenya as small innovations to improve climate resilience.

Kremer’s broader pitch was for meta-innovations: designing institutions to promote new innovation, including two areas he’s worked on in the past. The first is open, tiered, evidence-based innovation funds that give out small grants to pilot new ideas and successively larger funds to scale up successful ideas. The second institutional structure Kremer highlighted was “advanced market commitments”, like the contract offered by Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, to procure a minimum quantity of doses at a given price to anyone who could produce a pneumococcal vaccine in the 2000s.

The pandemic offered lots of economics lessons (and some unsolved political economy problems)

Vaccine equity was a problem, for a starter. Mushfiq Mobarak presented data showing that every low- and middle-income country surveyed reported lower vaccine hesitancy than the U.S. Yet even by the “end” of the pandemic, vaccine coverage remained below 20 percent in, e.g., most of sub-Saharan Africa.

To blunt the economic impact of pandemic shutdowns, developing countries were unable to finance social safety net programs on the grand scale seen in much of the OECD. It’s unclear if that will be any different next time around. Joana Silva presented evidence from Brazil that weak social safety nets failed to offset the damage from economic shocks to firms, leading to long-term impacts on workers’ employment and earnings.

Meanwhile, negotiations around a pandemic treaty have so far failed, and the World Bank’s pandemic fund has only raised $2 billion of its target $10 billion per annum.

Schools closed for too long. Norbert Schady presented data on learning loss during school closures, and recovery since then. Given COVID’s low infection fatality rate among children, these educational harms seem to have been almost entirely unnecessary, though the panel noted that next time may be different with a different pathogen.

So why did schools close for so long? That wasn’t entirely clear from the panel discussion. The two years of school closures in India, the Philippines, and Uganda came despite obvious harms to education outcomes and despite early evidence that Covid had a low infection fatality rate among children. There was also public outcry to reopen schools, at least in India and the Philippines. Navigating that political economy next time will require quite a bit more than education experts simply stating, “don’t close schools.”

Day 2

The productive inclusion of historically left out populations, in particular women and youth, is smart policy

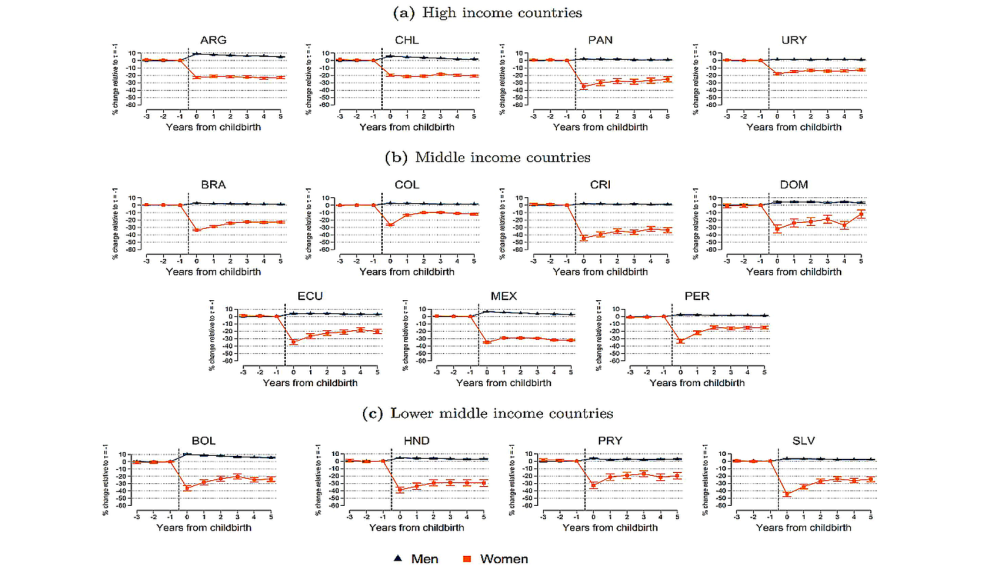

Women and youth are often disproportionately affected by poverty—and left out of the workforce. In their plenary addresses on day two, Raquel Fernández showed data from Latin America and Ashwini Deshpande from India on how and why women’s labor force participation lags that of men.

Two things particularly jumped out in the data from Latin America:

- The gender gap in labor force participation is widest for those with secondary schooling, which in turn is the highest level of schooling attained on average in many Latin American countries.

- There is a large motherhood penalty across the continent. Intriguingly, Fernández asked us not to think of this as a “penalty” as it might be reflective of choices made by women (choices related to schooling, timing of childbirth, stepping out of the labor force to raise children, etc.), but surely at least some of these “choices” are in fact shaped by strongly patriarchal norms. We found ourselves asking what “choice” actually means in this context.

Figure 3. The “motherhood penalty” in labor force participation across Latin America

Source: Reproduced from Raquel Fernández, ABCDE 2024 presentation

On the subject of norms, Deshpande highlighted the role of regressive norms in keeping women out of the labor force in India. But strikingly, she also showed that a recent decline in female labor force participation in India has been driven by a lack of jobs in agriculture, which is still the single largest employer of Indian women. So, there’s a bit of a chicken and egg problem here it seems: on the one hand, the productive inclusion of women may spur economic growth, but to spur that economic growth, we need jobs.

So, how does one “economically empower” women and youth and why, in fact, are they left out in the first place?

A very popular policy solution for the economic empowerment of women and youth is the social safety net. Women and youth are often the most cash constrained members within a household. As such, many policymakers believe that lifting that cash constraint will bring more women in the productive workforce. Cash transfers targeted at women are, thus, the policy instrument of choice, reaching over 400 million households worldwide in a typical year. In her plenary address, Karen Macours highlighted the long-term gains from such transfers, especially for the human capital accumulation of youth. Some key takeaways from her address and the panel that followed:

- Both Macours and Shalini Roy showed that cash transfers can improve household consumption, human capital accumulation by youth, women’s economic outcomes

- These two speakers also highlighted that the improvements to outcomes can persist well after the end of the program

- This said, Kehinde Ajayi discussed how in many patriarchal settings, teen girls face many simultaneous constraints, and empowering them may require several complementary approaches, not just a cash transfer

- In many LMICs, the quality of education leaves much to be desired. Isaac Mbiti and Andrew Zeitlin showed how apprenticeship can be a fruitful way of helping the youth acquire skills that have significant labor market returns

- Zeitlin highlighted the potential for such skilling programs in refugee settings and Mbiti showed us an instance where the apprenticeship led to lasting economic gains

- Teresa Molina presented evidence from the Philippines’ COVID response on how existing safety net infrastructure can be an efficient way of getting aid out quickly during emergencies

- But, as Owen Ozier showed, sometimes even impressive program impacts dissipate once the program ends. Eeshani Kandpal suggested that this is because often impacts are mediated by social norms and their impact on the household bargain

- Oyebola Okunogbe further highlighted—with data from a graduation program in Nigeria that led to unexpected gains for youth within targeted households—that intrahousehold resource allocation decisions can be an often-overlooked but important aspect of program heterogeneity.

It’s important to distinguish between the financial cost and the social cost of safety nets

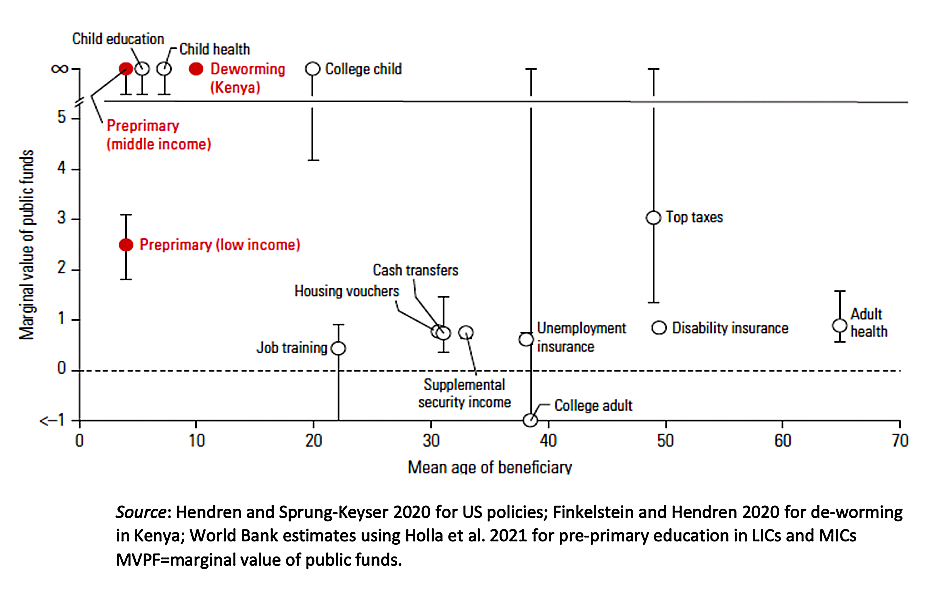

One thing that struck many in the audience on day 1, including us, was Indermit Gill’s take on cash transfers. His slide, which we’ve reproduced below, made the case that “education and health provide much higher returns than cash transfers.”

Figure 4. The marginal returns to various social investments at different ages

Source: Reproduced from Indermit Gill, ABCDE 2024 presentation, based on the World Bank Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report

- As Macours noted in her plenary address, specifically in response to Gill’s presentation the previous day, social protection systems in LMICs serve other functions beyond generating human capital. They often have multiple goals with poverty alleviation being a central one

- Taking these estimates that Gill reported at face value, a rational policymaker might well want to put all of her money on bed nets and deworming pills. To be clear, these are worthy investments but are they the way out of economic stagnation?

- Cash transfers are inherently different from public investments in health and education. Cash transfers are, first and foremost, forms of redistribution. The social cost of a $100 cash transfer is thus not $100; it is whatever the administrative cost of implementing the transfer is. So, any comparison on value for money terms should compare the overall cost of health and education interventions to the administrative cost of a cash transfer

Gender norms are both cause and consequence of economic change

But cash is far from the only constraint that keeps women out of the labor force. A lively exchange between Fernández and Deshpande highlighted how difficult it is to predict when and how norms might change. Sometimes, norm-driven behaviors, such as investments in girls’ schooling, or their marital and fertility decisions don’t change with income or information. Deshpande highlighted this challenge with examples from India. At the same time, as, Fernández countered, there has been rapid growth in social acceptance of homosexuality, even same-sex marriage, including in many LMICs. The difficulty of knowing when a social tipping point is reached is thus one of the challenges that a policymaker seeking to increase female labor force participation must contend with. Interestingly, some evidence suggests that cash transfers can actually change norm-driven behaviors such as intimate partner violence and women’s access to contraception and in a matter of months, rather than years or decades. But we saw how other major barriers that keep women out of the labor force include:

- Pamela Jakiela shed a spotlight on how we don’t even measure or seek to understand the impacts of childcare on women’s labor force participation. She also asked us “what do fathers do anyway?” with the answer often being, “not very much” in the sorts of settings that were being discussed

- Nishith Prakash highlighted how costly the sexual harassment of women in public spaces can be to women’s economic empowerment. To be sure, getting women into the labor force is far from the only or even the main reason to prevent sexual harassment, but it is a great co-benefit of making public spaces safer for women

- S Anukriti talked about the importance of family structures, with evidence on how disapproving in-laws can limit women’s agency (more of those troublesome norms…). Intriguingly, in her work, a small cash incentive can help bring mothers-in-law on board with greater autonomy for the daughters-in-law. Money can’t buy everything, but at least in this instance, it can buy your mother-in-law’s approval!

- Finally, Rachel Heath used data from the tragic Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh to talk about the role of poor working conditions in industries dominated by women in keeping many women out of the labor force. She highlighted how international pressure can improve such working conditions and lead to sustained gains for women’s economic inclusion

We won’t attempt a neat wrapper that ties together everything from sovereign debt and climate finance to cash transfers and gender norms. The theme was “the great incoherence”, after all. The topics ranged broadly, and there was no attempt to reach consensus here. But ABCDE remains interesting for forcing the academic research world to confront DC policy debates, and vice versa. Even when the research didn’t translate into tidy policy lessons, that felt like a healthy collision.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Mission and Values

We work to reduce global poverty and improve lives through innovative economic research that drives better policy and practice by the world's top decision makers. We strive for excellence and intellectual rigor and believe global prosperity starts with smart policy based on evidence. Our work is nonpartisan and our recommendations are not influenced by our funders. We are willing to challenge powerful institutions and the status quo for better development practices.

We are committed to transparency, diversity, and professional and personal integrity. We recognize the inherent dignity of all persons and pledge ourselves to creating and maintaining an environment that recognizes and respects diverse groups of individuals and their experiences. We value mutual respect, a collegial work place, and a healthy sense of humor. Explore our work on diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Our Work

CGD is currently focused on the following areas critical to development progress:

- Global Health Policy

- Migration, Displacement, and Humanitarian Policy

- Sustainable Development Finance

- Education

- Governments and Development

CGD’s Impact and Influence

Impact can take many forms—from shaping the academic consensus to turning proposals into policy. Sometimes, realizing the full potential of a good idea means letting it flower elsewhere and we take pride in our role as an incubator of initiatives—like the Energy for Growth Hub and Labor Mobility Partnerships—that first take root in CGD. CGD has helped to change global policies and practices, and has made a real difference in the lives of people in the developing world. Learn more about our impact here, and read our latest Impact Report here.

Our Leadership

Get to know our President Masood Ahmed, our Chief Operating Officer Mark Plant, and our larger management team. You can find our staff directory here.

Our Board

CGD’s Board, led by former Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers, includes influential leaders from the worlds of development, policy, finance, and academia

- 1158 reads