Another Country Director Bites the Dust

A few weeks from now I will be leaving my job as the Country Director for Next Generation Nepal (NGN) and returning to my native city of London. Working for NGN was – and is still – a dream job for me. As I prepare to leave, I have begun assessing what NGN has actually been able to achieve over the past five years. Have we been able to make a difference in the lives of children being trafficked into abusive Nepali orphanages?

In this article I talk about how and why NGN and our partners decided to address the problematic issue of orphanage volunteering in Nepal. I then go on to suggest a way forward for how to try and end orphanage trafficking in Nepal.

Idealistic Beginnings

When I started my position at NGN in 2012, my idealistic predecessor was pretty burned out. Perhaps it was his tiredness speaking when he told me, in no uncertain terms, that he had reached the absolutist conclusion that NGN had to completely end child trafficking to orphanages. Furthermore, he told me it was my job to do this. So no pressure then! Anyone who lives in Nepal knows it is a tough country to work in. “One step forwards, two steps backwards” was a phrase an experienced friend told me as she tried to mediate my enthusiasm towards this crazy goal. Indeed, I looked at NGN’s very modest budget, alongside the plethora of complex social reasons as to why children are trafficked, and I realised that we would have to think very creatively about how to approach this problem if we were to come even close to being successful.

On the positive side, we worked quite well with the Nepali Government to rescue trafficked children from abusive orphanages. We also did a good job at rehabilitating them, finding their families and returning them home (which is undoubtedly very important for those individual children whom we help). The problem was that for every child we took home, the traffickers were displacing another fifty. The odds were stacked against us. We were swimming upstream. So I figured that if we were to make any dent in this problem whatsoever then we had to do something to tackle the causes for why these children were being separated from their families.

Why Children are Trafficked into Orphanages

The causes were complex. Children in Nepal had been being displaced and institutionalized on a large scale since the civil war which ran between 1996 and 2006. The phenomena began in Humla district where guerrilla fighters had conscripted children into the Maoist rebel army. In these horrific circumstances some kindly “social workers” – who in fact were really traffickers – promised the children safety from bullets and a bright future if their families paid them some money to take them out of Humla to study in good “boarding schools” in Kathmandu. When the civil war ended, the trafficking continued on the false promise of a fast-track route for children out of poverty through a quality education. The boarding schools of course were not what they seemed; they were in fact under-resourced children’s homes, or so called "orphanages", where the children were abused and neglected, and presented as orphans or destitute even though they still had living families in their villages who were capable of caring for them.

The traffickers then realised the fundraising potential of promoting these “orphans” to foreign tourists and donors who came to Nepal looking for adventure and a way to channel their genuinely philanthropic intentions. Hence the term “voluntourism” being used to describe this phenomenon. The traffickers realised that the more poor, destitute and sick the children in the orphanages appeared, the more money could be solicited from the well-intentioned but naïve foreign voluntourists who were unaware of the murky world they had become embroiled in. The business-model worked well, and the orphanage business boomed. Many people in positions of power in Nepal were making good money from the business, so despite worthy high-level rhetoric to the contrary, there was little incentive to change it.

The (Almost) Perfect Plan

So I thought long and hard about what we could realistically do with our tiny budget and small staff team. We could fund education and livelihood projects in the villages, to create better facilities so that families felt less compelled to let their children leave, but many NGOs were already doing this with far bigger budgets than we had at our disposal, and it was not ending child trafficking… at least not yet. We could try and tackle the corrupt system which allowed all this to happen, but corruption was endemic in Nepal, and more powerful agencies than us had tried and failed to change this.

NGN was just a small grassroots NGO, run by simple yet idealistic people who had once naively thought in our youth that we could “change the world” by volunteering for NGOs, only to discover that in reality international development was not that simple. And then it hit me: we were still at heart those same idealistic volunteers – and this was our USP. We could tackle orphanage trafficking by taking on what we knew best: orphanage volunteering. We had all volunteered in orphanages when we were younger, and we all knew why people like us wanted to volunteer in orphanages, so this was what we could change. If nothing else we could put the issue of orphanage voluntourism on the international development agenda.

Why Orphanage Volunteering is Harmful

For those who are unfamiliar with the harm caused to children by orphanage volunteering, there are a wealth of resources which explain the problem. In essence though, predominantly well-meaning fee-paying volunteers actually create the incentive for traffickers to separate children from their families and place them in orphanages so that they can be used as poverty commodities to raise funds. Not only does this deprive the children of the childhoods they deserve – and need – in the loving care of their families and communities (where most of their cognitive, psychological and emotional development happens); but most of the money donated by the volunteers ends up in the pockets of the traffickers and the orphanage managers. Furthermore, even in so called “good” children’s homes, a rotating roster of unskilled volunteers exacerbates psychological attachment disorders. For children who have already undergone the trauma of being separated from their parents at a young age, they are subjected to a childhood of being loved then left by hundreds of volunteers who come and go from their lives, like visitors to a zoo. Children who grow up in orphanages are much more likely as adults to suffer from depression, anxiety and an inability to form healthy emotional relationships; are more likely to be sexually exploited; are more likely to engage in prostitution and crime; and are more likely to commit suicide.

What We Actually Did

I started by asking some of our staff and volunteers to document everything they knew about orphanage trafficking in Nepal, and its links with volunteering. We began to notice some interesting patterns, such as the startling fact that – at that time – 90% of the children’s homes in Nepal were located in the top five tourist districts of the country, and this certainly did not correspond with levels of need in those districts. We also collated real-life stories of orphanages where children had been exploited whilst volunteers were being used to raise money. When I was asked to present these findings to a group of foreign diplomats at a high-level meeting in Kathmandu, I was pleasantly surprised that they took it really seriously, and many of them changed their travel advice, warning their citizens not to volunteer in orphanages. UNICEF then became interested in the issue and helped us to promote our published report, The Paradox of Orphanage Volunteering, at a high-profile event. Similarly we were given tremendous support by a global coalition of organizations called the Better Volunteering Better Care Initiative who – unbeknown to me – had been set up exclusively to tackle this issue and help groups like us on the ground. Suddenly we were part of a global coalition of like-minded organizations all striving to end orphanage voluntourism and promote ethical volunteering alternatives.

At the same time we began to link with like-minded people and organizations within Nepal. There was The Himalayan Innovative Society, our local partner, who helped us collate all the data we needed. There was Terre des Homme who had laid the path for us with their ground-breaking work on paper orphans. There was the US Embassy in Nepal – and indeed other embassies – which valued our grassroots knowledge and showed its support through its travel advice, and by including this issue in its annual Human Rights Report. Then there were our old friends at The Umbrella Foundation who were going through a process of changing their volunteering program away from working directly with children; and a small Australian group called Forget Me Not that had been scammed by orphanage traffickers, and as a result had totally changed the direction of their NGO to tackle orphanage trafficking instead. At the radical end of the scale there were Freedom Matters and Sano Paila who picked a fight with the “baddest” orphanage of all (which name I will not mention because the man who runs it is seriously dangerous!) and almost won. And then there was the thoughtful campaign group, Learning Service, which had created a brilliant philosophy to encourage learning about the local context before rushing in as a volunteer. From the tourism industry there was socialtours.com who took the lead in promoting the fact that they do not practice orphanage volunteering. Then finally there was a wizened Irishman – there always has to be one – called Declan Murphy, who had been tirelessly evangelizing about these issues for many years before we had. There were more people too, and I cannot possibly list all of them here. NGN was not fighting this battle alone – we had comrades who shared our vision.

The Great Nepal Earthquake of 2015 was to have a huge impact on the problem, in ways none of us anticipated. The world’s media flocked to Nepal to cover stories of collapsed buildings, and when they had photographed and written all they possibly could about collapsed buildings, they started looking for human interest stories. The idea that child traffickers would take advantage of a disaster, such as a civil war or an earthquake, was an anathema to people in foreign countries, and the journalists could not get enough of it! By the summer of 2015 we were turning journalists away due to sheer exhaustion on our part, but the press coverage of orphanage trafficking and voluntourism in Nepal just kept coming and coming. To respond to the growing interest by tourists and other people we started running weekly awareness raising talks in Thamel, the tourist district of Kathmandu, and by late 2015 the new edition of the Lonely Planet Guide to Nepal included a discussion on the problems with volunteering in orphanages, and we knew we had reached an important milestone – there was no going back from here.

We had won! All the orphanages closed. The traffickers were arrested en-masse. All the children walked free form their chains and ran home to their waiting mothers and fathers in the mountains, and Nepal announced a new public holiday to celebrate… err… I wish this had happened, but obviously it did not. The sad truth is that, despite all we have achieved, at the macro level not much has really changed for institutionalized children in Nepal.

Unexpected Consequences and a Polarized Discourse

Unlike the final scene of my favourite Indiana Jones film where the stolen children escape back home to their loving families from the evil human-sacrificing Kali worshippers, I am afraid there is not yet a happy ending to this story. NGN may have rescued and reintegrated hundreds of individual trafficked children, and together with our partners we may have started the conversation about one of the biggest contributing factors to orphanage trafficking in Nepal, but overall there are still no discernible differences to the numbers of children living in orphanages, so far as I know. Furthermore, it is unclear whether we have made any major dents in the child trafficking business itself. Unfortunately I have so far failed my predecessor’s challenge.

In starting this debate we have received incredible levels of support and encouragement from thousands of caring people around the world, and we are now even witnessing high profile celebrities, such as JK Rowling, speaking out about the issue for the first time. But we have also made a lot of people very unhappy. A few months ago, late one night, I received a drunken message from a friend of mine to tell me that I was “pissing him off” for caricaturing all children’s homes as “bastards” and all volunteers as “abusers” (which I certainly do not do). Several people have also said to me that they think we are creating a bad name for the “good” children’s homes in Nepal. They say that the children in their children’s home have no choice other than to be there, and that the volunteers who support the children bring much needed love into their lives. These are sadly not isolated incidences for me these days, and whilst I do not agree with the criticisms of my detractors, I can see that our campaigning has clearly touched a nerve. As a wise person once said: first they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, and then you win. But we have not won yet.

The criticisms I receive do stay with me and I think about them a lot. Most of those who criticize us are not “bad” people, and many of them share our vision for a better world for vulnerable children, but they have a different view of how to achieve this. It concerns me that such a polarizing discourse has evolved amongst people who are essentially “good”. So in the last section of this article I want to set out my own thoughts for where Nepal needs to go if it really wants to end child trafficking to orphanages.

How to End Orphanage Trafficking in Nepal

- The “good guys” need to work together – Personally I align myself with international law and sixty years of academic research which shows that children’s homes are not the best places for children, except as a last and temporary resort. However, I am also a pragmatist, and I do understand the realities in Nepal and accept that, so far, nobody has been able to develop adequate foster care services or inclusive education. Because of this there are extreme situations in Nepal where some children simply cannot live in family-based care settings. Indeed, there are some very good children’s homes in Nepal, and they need to be supported. But this is not a reason to give up on working-towards family-based care as a long-term aim. This is my view, but not everyone agrees. However, whatever your view is on this contentious subject, the chances are that you do genuinely want the best for children in Nepal, and if that is the case, then we need to find ways of working together, rather than arguing amongst ourselves. Let us debate, discuss and look for solutions, but let us save our anger and frustration for the criminals who traffick and abuse children, as well as for the unscrupulous volunteering organizations that have created a global market in which orphanage voluntourism and family separation have become normalized (see below).

- The focus of our advocacy efforts should shift towards targeting the powerful and unethical volunteering organizations – Up until now a lot of the focus of NGN’s publications and stories, and in deed those of other organizations and the media, has been about the “corrupt” Nepali traffickers and orphanage managers, and not about the organizations in more powerful “Western” countries which created the market for orphanage volunteering in the first place. As Vicky Smith argues, it was these commercial organizations which created the notion of providing foreign volunteers to local not-for-profit organizations to help them raise money, and the local organizations simply responded, which eventually resulted in a harmful and criminal orphanage industry. We need to become more sensitive to the power and race differentials in these debates. We need to have some empathy with the so-called "traffickers", many of whom are from extremely poor and abusive backgrounds themselves and, to some extent, believe that they are doing a service to the children they are displacing by bringing them to "developed" cities away from the poverty and hardship of the village. Why do we focus on the “evil Nepali criminals” who are responding to a Western-led demand, rather than the white-collar professionals in wealthy countries who created this demand? Is it because the white-collar professionals are too similar to us? Is it because we are legitimately scared of potential litigation from these same organizations (as Vicky Smith herself discovered)? Is it because “the other” in less-developed countries are easier and safer to demonize through an all-too-acceptable Orientalist discourse? Another trend of advocacy campaigns has been to blame the volunteers themselves. But are the volunteers also not the victims of the same marketing machines of these volunteering organizations? Maybe we need to re-think who our advocacy efforts should be directed at. I believe the focus of our campaigns needs to shift more towards these powerful commercial volunteering organizations which, despite the evidence, refuse to change and continue to perpetuate this problem.

- We need to remain steadfastly pro-volunteering, and find ways to make voluntourism work – Although I argue that we need to challenge the powerful unethical volunteering organizations, I am in no way suggesting that this includes all volunteering organizations. To the contrary – I believe we need to continue to remain pro-volunteering, and we desperately need to support volunteering approaches and organizations which genuinely use ethical volunteering models. This means that volunteering organizations like People and Places, Intrepid Travel and Travel4Change should be better promoted because of their ethical stance. I really do believe that volunteering is a force for good in the world – both for the volunteer and for the local communities they work with. If we can re-frame voluntourism away from a donor-beneficiary relationship towards an equal dialogue and learning experience, then there is definitely a place for it in which everyone can benefit. Voluntourism is a reality in the twenty-first century globalized world. There is a danger that if we become overly idealistic and argue for it to be stopped completely because of its problems, then we will definitely fail. Instead we need to find ways of resolving its problems and making it work in ways that do not harm people.

- Orphanage trafficking needs to be legally recognized as “trafficking” – One of the reasons that orphanage trafficking still gets such little attention both within Nepal and globally (compared to other forms of trafficking such as sexual exploitation, labor trafficking, bonded labour etc) is because it is still not legally recognized as a form of trafficking in the influential US State Department Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report. Whilst many NGOs and the media talk about it as “trafficking”, the TIP Report fails to mention it, and hence many donors and larger organizations do not allocate significant resources towards it. There is now, however, hope that this could change thanks to an Australian lawyer called Kate van Doore who has made the first legal argument to connect volunteering with orphanages and child trafficking. If she can succeed in persuading the powers-that-be that this problem should be included in the TIP Report, then this could be a game-changer in terms of making the issue an international development priority.

- We need to work holistically – We need to always remember that orphanage trafficking is a symptom of a much bigger development challenge. Until we can ensure there is quality education in rural areas, thriving local economies, women’s empowerment, adequate support services for people living with disabilities, effective social workers for vulnerable families, and effective governance and legal systems, there will always be a high risk of children being trafficked. Similarly, for as long as there is inequality in the world, there will be a desire by wealthy backpackers, short-term missions trips and donors to support projects in less-developed countries, many of whom will choose orphanages as their target beneficiary group. We need to recognize that these issues are complex and inter-connected, and we need to work to resolve them holistically and in partnership with others. This means people from the child protection sector, international development, governments, academia, the tourism industry, faith groups and other sectors all working together, with mutual respect for each other’s skills and knowledge.

- We need to keep saying the same messages over and over and over again – It can sometimes feel frustrating for those of us who understand and believe in this cause to keep saying the same things over and over again: “Most children in orphanages are not orphans”, “children’s homes are not the best solution for vulnerable children” and “orphanage volunteering is harmful because of x y and z“, etc. However, this is exactly what we must do. It is impossible to monitor the impact that our message has on each and every individual who hears it. Some people will listen and ignore it, others will listen and forget it, and for others it will have a profound effect. For some people it may result in them pushing to deinstitutionalize an orphanage they are connected with, or maybe telling someone else about the problem who has significant influence with a major donor. The work we are doing now is laying the foundations for more noticeable high-impact change in the future. We must patiently and diligently continue extolling the same messages over and over again until we reach a tipping point. Maybe with JK Rowling’s recent intervention we already have?

- We need to be patient – “One step forwards, two steps backwards” was the phrase my friend used to describe Nepal. Indeed, it does feel a bit like this sometimes. But if we did not believe we were slowly and incrementally helping to change the system, then we would not be doing the work we do. The problem is our own egos (and perhaps our donors!) which want to see a tangible impact soon. We need to let go of our egos (but perhaps not let go of our donors!) and do what we do for the sake of the journey as well as for the destination. Stephen Hawking sums up this approach well in this piece he wrote on “cathedral thinking”.

And Finally…

And finally, to conclude this article – and I say this very seriously – if you have not watched Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom then I strongly recommend you do so. It is a pretty crazy film. But if we do not strive to achieve crazy goals, then we will never achieve them. And on this note, it is goodbye from me to Nepal, and thank you to everyone who has helped us to get as far as we have. I wish the best of luck to the next generation of activists whom, I believe, will completely end orphanage trafficking in Nepal.

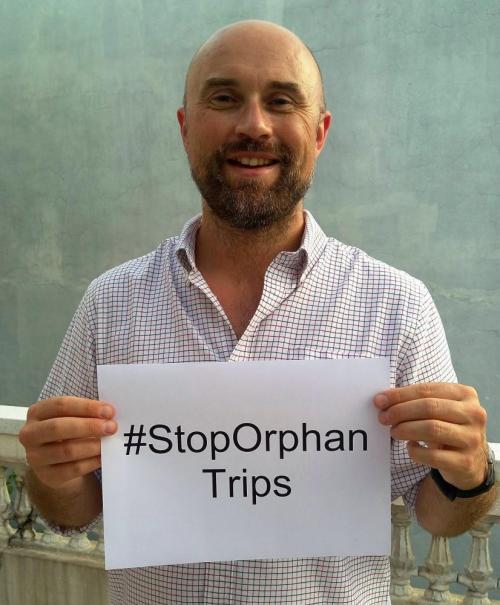

Martin Punaks is the Country Director for Next Generation Nepal, a US international NGO with a mission to prevent the trafficking of children into abusive children's homes and rebuild family connections torn apart by traffickers. He has lived and worked in Nepal since 2011. He will leave his position as NGN Country Director in October 2016 to return to his native London, UK. To learn more about NGN’s approach to ethical volunteering see here. #StopOrphanTrips

Add new comment